Sport dropout: Why do young athletes leave sport programs?

If youth sport is a universal good then we should know more about why athletes dropout of our programs.

There are three main reasons that youth sport is seen as a universal good. First, sport teaches youngsters skills that will help them maintain healthy lifestyles long after their youth sport days are finished. Second, sports are a socializing influence for youth much like education. Third, youth sports are the foundation of a country's performance in international events. Youth sport is an important part of many cultures and the health of youth sport programs is or should be on the radar not only of national sport governing bodies (NGBs) but social, educational, and economic watch dogs as well. It's not a good thing when youngsters dropout of sports. If we can find out why they do this it might help us create better programs.

Youth sports are programs organized to teach skills, and provide various levels of competition. They exist in multiple contexts such as short-term recreation programs, longer lasting activities that take place in year-round clubs, and education based teams in high schools. The scope of some of these programs is wide and requires years-long participation with goals of developing young athletes so that they progress through levels of competition, perhaps leading to further participation in college, professional, or international ranks. Youth sports also includes programs with a much narrower focus, one not aiming at future performance but rather short-term enjoyment, socialization, and physical activity.

Previously I wrote a short summary about the phenomena of burnout, which is often paired with dropout as if they are the same thing. Burnout is a form of dropout but has its own specific signature and affects athletes in much different circumstances than those we're concerned with when discussing dropout. This article is not about burnout.

Burnout is a psychosomatic state characterized by fatigue, a high level of perceived stress, and a reduction in motivation. It typically occurs in athletes who have participated in a sport for an extended period and who have experienced some level of perceived success or satisfaction.

What draws youngsters to join youth sport?

It's not the quest for Olympic gold as some may think. The broad gamut of youth sport programs makes it difficult to zero in on the motivational triggers that attract millions of participants every year, or to design a sort of one-size-fits-all curriculum that would make youth sport the fast food of the sports world. Successful coaches and NGBs may not know the different reasons why athletes are there, but they are able to accommodate various motivations and guide young athletes in a general direction of learning, improving, and competing in their sport. This is the process of investment:

Investment can mean a lot of different things though. Sport administrators err when they organize grassroots programs on the assumption that athletes join with dreams of Olympic glory. The reasons why youngsters get involved with sport initially are based on fun, convenience, fitness, friends—almost anything except the sport itself.

Investment occurs after the athlete gains some of the necessary skills, becomes fit enough to actually play the game, and participates often enough to gain experience. Parents also become invested mostly due to their child's interest but also because of aspects affecting other parts of family life. If NGBs can consistently give families a reason to stay involved they will. (Retention and training age, March 2021)

Just as there are many reasons why youngsters join sport programs, there are probably just as many reasons why they leave. Sociologists have been studying things like this for many years and have identified both the whys and, perhaps more importantly, the whens of youth sport dropout.

Know the numbers

Metrics such as dropout and retention need to be tracked in cohorts for them to make any sense. Figure 2 is from that article and shows the 2016 retention metric by age for an imaginary NGB. Dropout is derived from the retention metric. For example, the 1-year dropout rate for 7-year-olds in Figure 2 is 25% (since the retention rate is 75%), so seven athletes who joined the sport in 2016 dropped out within the first year, eight athletes from that same cohort dropped out within the first two years and so on. Context is important, so check out the article linked above to get a better idea of why the analysis is done this way.

Sport dropout occurs when athletes terminate their sport participation prematurely. Some attrition is to be expected but how much is normal can only be determined after analyzing several years of data. Additionally, all athletes eventually leave their sports. Whether or not we call this dropout depends on when they do it. For many athletes the transition of leaving high school for college is a natural time to end organized sport participation. Although the popular narrative is that high school athletes are preparing to be college athletes, the numbers don't support this. Only 6% of high school athletes compete on college teams, so for most young athletes the high school/college transition is a normal time to leave organized sport.

Why do youngsters leave sport?

Some athletes dropout simply because they are not enjoying themselves. Anyone who works with young athletes knows that not all children who join a sport are going to stick with it. They may join basketball, decide they don’t like it and enroll in volleyball, or track, or martial arts. They’re feasting at the youth sports smorgasbord, trying a little of this and a little of that until they find something they really like. Reasons for withdrawal vary by age, sex, level of participation, number of sports sampled, and other variables. By combining these reasons with retention and dropout statistics an NGB may be able to develop a fuller understanding of how dropout is affecting their sport.

Classification model in a longitudinal study

The reasons athletes have for joining an activity can have a lot to do with the reasons they leave. But if we ask athletes why they leave we get a predictable list of reasons: not having fun, didn't like the coach, wasn't good enough, no time with friends, etc. By itself, this kind of list is not very helpful unless we understand a little more about the athletes who provide it.

One way to do this is to identify athletes as specific types of sport participants, and characterize the nature of their participation. The Linder model1 was proposed in a longitudinal study in 1991. It added depth to the mostly superficial reasons given in sport leaving surveys. In identifying athletes and how they leave sport activities Linder and Johns proposed three basic athlete types:

Leavers are athletes who drop out of one particular sport but are involved in at least one other.

Dropouts are athletes who leave sport completely.

Transfers are athletes who switch from one sport to another.

The model also characterizes an athlete’s participation:

Samplers are athletes that can be described as simply giving the sport a try.

Participants are athletes with low to high levels of regular participation.

Elite participants are athletes who compete at the highest level.

By combining the dropout type and participant level with the usual kind of information collected in dropout studies (sex, age, reasons for leaving) a deeper understanding of the dropout phenomenon can be developed.

A 10-year retrospective study published in 2002 used the Linder model and found that sport dropout was a common occurrence in a group of Canadian youth (N=1387; 666 female, 721 male); only 5% of these athletes were still involved in the same sport they started with 10 years earlier. The typical respondent was still participating in one or more sports at the time of the study. Many of them had dropped out of a sport and joined another several times throughout the 10-year period.

Using only the type of participant classification, the average athlete in this group participated in 3.9 sports over the 10-year period, dropped out of 2.5 of them, and participated for an average of 3 years in each dropped sport. If results are broken down by sex alone, girls participated in fewer sports than boys, dropped out of fewer of them, and participated in each for a shorter amount of time.

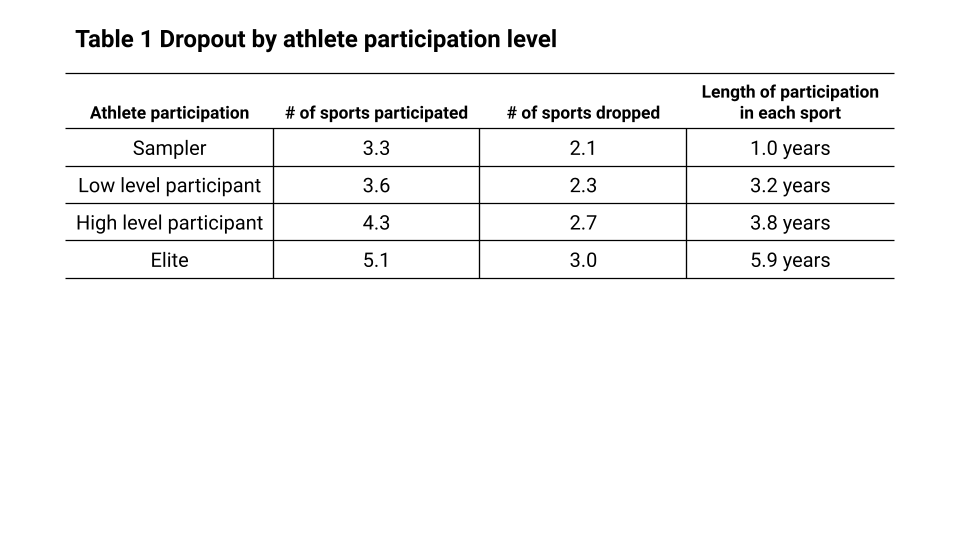

Table 1 shows what one might expect when participation level is incorporated into the results. Students in the sampler and low-level participant categories participated in the least number of sports during the 10-year period (3.3 and 3.6 sports respectively), dropped a greater proportion of them (2.1 and 2.3), and participated for the least amount of time in each (1.0 and 3.2 years). High- and elite-level participants also had predictable results participating in 4.3 and 5.1 sports over the 10-year period; dropping out of 2.7 and 3.0 sports (a smaller proportion than that demonstrated by the sampler and low-level categories), and participated for the greatest amount of time in each sport (3.8 and 5.9 years). The differences were significant between all of the dropout types.

In Table 2 it's interesting to note that the importance of enjoyment and efficacy feelings diminished from the sampler to the elite-level participants. This highlights two points: First, the meaning of 'fun' is often dependent on who is having it. In many early studies on sport dropout "not having fun" was always near the top of the list of reasons youngsters give for dropping out of sport, however no operational definition of fun was offered. In research it's important that terms have definitions, so assuming that we all know what fun is or that we all define it the same way is a bad assumption. Is there a definition of fun that can be used for various ages and athlete types? Here's a suggestion: Fun is an achievable challenge.

Second, and this will sound obvious once you think about it, perhaps the reason feelings of efficacy were not as important to elite athletes as they were to the samplers is that elite athletes had developed the skills necessary for the sport throughout their years of participation.

Dropout among invested athletes

Another Canadian study2 selected a group of 50 swimmers, 25 of whom were currently engaged in the activity and 25 who had dropped out, and who also were: between 13 and 18 years of age, participated in the sport for more than three years, and trained for more than 10 hours per week. In this way low-impact groups (samplers and low level participants) were eliminated. This allowed researchers to investigate the dropout phenomena on athletes already invested in their participation.

One of the variables they studied was the athlete's age of specialization. This is an important variable because it can change the nature of an athlete’s participation in an activity even if all other variables are the same. For example, a 12-year-old athlete may be similar to other 12-year-olds on a sports team except for additional practice time, attending training camps, or private instruction. These additional activities can significantly alter that particular athletes' sport experience when compared to other 12-year-olds. By isolating this in the study the researchers could examine specialization as a dropout variable.

They found significant differences between the dropout and engaged swimmers in terms of training time, “Of particular interest is that while the dropout and engaged athletes’ start age in competitive swimming did not differ significantly the structure of their early involvement varied with dropouts demonstrating a clear pattern of early specialization”. In other words, dropout athletes in this study tended to specialize in the sport earlier than those who were still engaged. The specialization was demonstrated across several variables:

Specifically, dropouts participated in fewer extracurricular activities and spent significantly less time in unstructured play swimming than engaged athletes throughout development. Dropouts also started dry land training significantly earlier than engaged athletes (age 11.4 versus age 13), had their first training camp significantly earlier than engaged athletes (age 11.8 versus age 13.7), and reached ‘top in club’ status earlier than engaged athletes (age 10.8 versus age 11.9).

Other physical factors included switching clubs and taking time off from swimming. Dropout athletes took less time off from the sport and switched clubs less often than engaged athletes. This is a sign that specialization is underway. Taking less time off from an activity may not indicate specialization per se but it is a clue that specialization is occurring, especially when grouped with other factors such as early dry land training, early training camps, and reaching the top of structured reward systems earlier than peers.

Athlete satisfaction and parent involvement

Other studies showed that athlete satisfaction and parent involvement or interest in the activity were key predictors related to dropout. The athlete’s perceived confidence in their ability positively affected perceived value. This indicates that sport programs that focus on instruction and technical matters early in the athlete’s participation—thus increasing ability and self-efficacy—might later have positive effects on how long the athlete stays in the activity.

Also, a parent being involved in the activity was a positive indicator of a child’s continued participation. Parent roles included volunteer coach, competition worker, fundraiser, or any number of other typical support roles available in youth sports. Children were unlikely to stick with an activity that the parents either did not like or showed no interest in.

Intrinsically motivated athletes stick around longer

A study of Australian youth gymnasts found that athletes whose needs were not being met were more likely to dropout than those whose needs were met. Most likely to dropout were those whose initial motives for joining gymnastics were extrinsic such as being popular with others or getting out of the house. These motives could be met by any number of activities so athletes with extrinsic reasons for participation had little incentive to remain engaged if their situation changed. Those with intrinsic motives for participation, such as challenge, competition, or fitness, were less likely to dropout if those motives were met, however, intrinsic motivation is something that is usually developed as athletes progress in an activity or self-efficacy increases, or as athletes get older.

The intrinsic/extrinsic divide in the gymnastics study also described the type of participant. Extrinsically motivated athletes were more likely to judge themselves in terms of comparison to others. If they felt that they were not meeting what they believed to be external standards then they were more likely to dropout of the activity. Those with intrinsic motives based their assessments of personal capability and success more on internal factors and were less likely to be affected by others who may be more skilled or have more success. Dropout for the intrinsically motivated group happened less. As a general proposition though, at younger ages children are motivated extrinsically and this gradually shifts with age toward intrinsic motivation. It's unlikely that older athletes would be motivated by extrinsic factors to any great degree.

Being able to identify both the type of dropout and the nature of participation of the athletes brings clarity to the dropout phenomena and adds dimension to the entire concept of retention in youth sports. Often, it seems that the only reason athletes ever leave a sport is that they are not having fun. This is a common reason for dropout, but there are also other factors in play that make the question of dropout much more complex.

The youth sport industry is fueled by the overwhelming belief that sports participation by youngsters and adolescents is a good thing. Youth sports have been anointed with almost magical powers to reduce childhood obesity, increase fitness levels, socialize children into their communities, and set youth off on the right track toward a life of good health, friendly competition, and a number of leisure pursuits to choose from as they get older. In addition to being a valuable socializing asset, youth sports are also the foundation of a country's success in international competition. But these two goals are rarely considered dependent on each other. Recreational, sport-for-all programs often disparage the long-term, somewhat professionalized training in commercial sport clubs. Likewise commercial youth sport programs dismiss recreational programs as inconsequential or ineffective.

Designing youth sport programs that address dropout issues will improve the experiences of many young athletes regardless of their level of participation. Good programs will also strengthen the base of athletes for NGBs well into the future. The parties concerned with these goals are usually two different groups. The NGBs are focused on elite performance and usually take the developmental levels of their sport for granted. The youth sports side of the equation usually doesn’t focus much on how early youth sport experiences can shape an athletic career. Both sides need to take the long view and realize that they are part of the same thing.

Linder, K.J. and Johns, D.P. (1991). Factors in withdrawal from youth sport: a proposed model. Journal of Sport Behavior, 14(1).

Fraser-Thomas, J, Cote, J, Deakan, J. (2008). Understanding dropout and prolonged engagement in adolescent competitive sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 9(5).

Excellent article, thank you Bill.