Overcoming diminishing returns in high performance sport

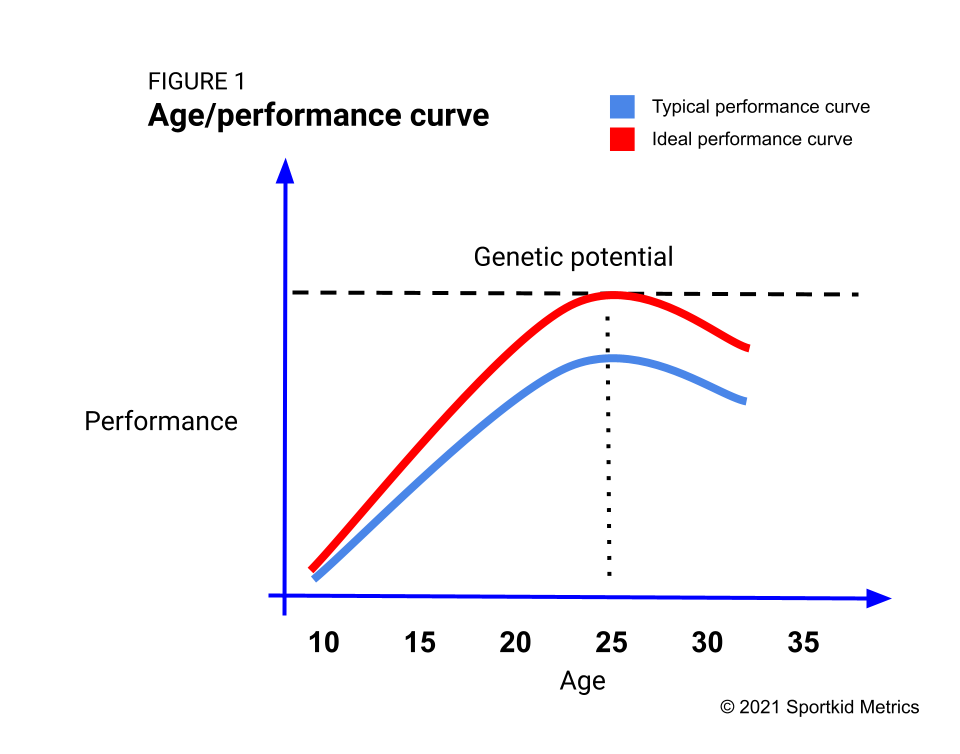

The age/performance curve shows why many elite athletes never reach their genetic potential. This article discusses ways coaches and NGBs can help more athletes perform at the edge of their ability.

At the beginning of one season while I was still a swimming coach I began to notice how cyclical my job was. At various times throughout the year I would write newsletter articles about the same things I wrote about the year before. Workouts were based on the same patterns I followed previously and the competition calendar looked a lot like it did every other year. The goal, of course, was to write better workouts, achieve better results—really just get better at everything—but it all had to happen within the same basic framework every year. There's nothing unusual about this, it's the way sport is.

In the 2022 sport seasons we are going to witness the result of what happens when patterns break. Thanks to the pandemic, sport was put on hold. Training was suspended or modified in ways that were neither voluntary nor ideal. Athletes who were able to train were often forced to use methods outside their traditional routines. What effect will these forced changes and improvised training practices have on performance? Only time will tell, but clubs and coaches are making plans to recover the lost training year.

Resources

How genetics influence athletic ability This article takes a deeper look into how genetics might affect sport performance. It discusses genetic potential more than I do in this article.

Pandemic recovery will help practitioners focus on the science behind the training by identifying how training effects were impacted by the changes and how athletes responded in terms of performance. Based on those observations they may hatch a few new ideas to inform future training. In other words, coaches will be forced to pay attention to something that they normally take for granted. The 'science' behind sport training is unquestionably accepted until it isn't and at that point usually something has occurred that raises questions about something previously accepted as fact. The training turmoil during the past year is such an event. In the coming months we may witness changes in how training is understood and delivered.

Think about how training elements we take for granted today became part of an athlete's preparation. In swimming, for example, there was a time when debate raged over the value of strength training, psychological skills were considered mysterious mumbo jumbo, and proper nutrition wasn't even on the radar. Things have changed.

The question now is will coaches and clubs go back to what they were doing prior to the pandemic or are changes in order?

Diminishing returns

High performance athletes and their coaches are well aware that improvement at elite levels is marginal. Two factors are primarily responsible for this. First, as an athlete's performance approaches his genetic potential greater training inputs are needed to achieve even minor improvements. Eventually ramping up training inputs results in no changes at all or, in some cases, negative changes. In the lingo this is known as the principle of diminishing returns, doing more but getting less.

Second, age plays a role. It's no secret that performance in sports is age-limited. Elite athletes of both sexes reach their peak performance around the age of 25 but there are exceptions.1 Metabolic factors such as V02max, cardiac output, and strength are vital to sports measured in centimeters, grams, and seconds (CGS sports); these and several other factors all decline with age and lead to gradual and permanent drops in performance. In team sports or in sports that are judged like diving or figure skating, metabolic factors are slightly less important since skill is the primary determinant of success. The decline is both less noticeable and less of a performance factor, at least for a while, which helps explain why athletes in team sports generally have longer careers than those in CGS activities. However, age always wins, it's just that the game is over sooner in some sports.

Genetic potential is heard often in sport and fitness circles but getting into the weeds of what this term means is outside the scope of this article, but here is a good overview of how genetics affects athletic ability. While genetic potential is not affected by training, reaching one's genetic potential certainly is. There are three rules to understanding how this works:

Although everyone has a genetic potential for athletic performance we do not know what it is. By testing muscle fiber type, VO2max, certain genes to determine fast or slow training response, and various other factors we can predict what type of athletic ability an athlete may have, but the bottom line is that no one ever really knows what their performance ceiling is.

Training is essential to achieving genetic potential or coming anywhere near it. Without training it doesn't matter what an athlete's potential is.

The training process needed to get anywhere near one's genetic performance potential is long and requires participation in comprehensive development over a number of years. The high performance training stage is certainly part of this process but the majority of training that will help athletes achieve their athletic potential occurs in developmental programs.

The principle of diminishing returns suggests that improvement diminishes over time as performance approaches genetic potential

Many elite athletes never reach their genetic potential. This is especially true when NGBs don't have a club system or are lacking adequate development programs for youngsters. Since elite status is relative, athletes in these NGBs rise to the top in their country despite poor training opportunities. But they do it without a comprehensive developmental background, thus as they age performance begins declining long before they have reached their genetic potential. Additional training inputs at this point can slow performance declines but additional improvement is unlikely.

Figure 1 illustrates two age/performance curves. An athlete who is able to follow the ideal curve (red line in Figure 1) achieves genetic potential before the negative effects of aging begin. The ideal performance curve shows an athlete achieving his genetic potential before age begins to take a toll. This curve results from comprehensive planning at all levels of development and can take 10 to 15 years to reach fruition. It includes age-appropriate training inputs throughout the entire time an athlete is engaged in the sport. It's a result of an NGB orchestrating the training, administrative needs of a club system, and competitive opportunities for athletes so that everything that has to happen actually does happen. This is difficult to achieve but it shows the kind of responsibilities that NGBs have to a national sport system.

The typical performance curve (the blue line in Figure 1) shows an athlete whose peak performance does not meet his genetic potential. The athlete in Figure 1 begins declining due to age before he reaches peak performance. This age/performance curve is far more common for a number of reasons, some of which cannot be controlled. One that can be controlled however, is the effort that NGBs put into creating and maintaining proper development schemes throughout the career span of an athlete.

Genetic potential is an idea; it's a way to describe the absolute limit of an athlete's performance. It cannot be accurately measured in any traditional sense, so no matter how well an athlete performs we will never actually know if they have achieved their genetic potential. However, based on the athlete's training history, the NGBs developmental framework, and various other factors we can make educated guesses about when an athlete has missed the mark.

As the pandemic moves into recovery, sport practitioners should ask themselves if athletes are given opportunities to achieve their best performances in the sport? Are NGBs implementing developmental frameworks that lead to elite level performance that includes athletes of all ages? Is the sport community working to get athletes on the ideal age/performance curve?

In the last newsletter I wrote about how clubs have their work cut out for them in this recovery. But it's not just clubs, everyone involved in delivering sport programs has a unique opportunity—probably within the next year—to help sport leap forward, to create programs that enhance young athlete enjoyment and performance in the sport, and to build an environment that allows athletes to know that when the time for retirement arrives they aren't leaving anything on the table.

The age where performance begins to suffer is an estimate, each athlete is different; some begin their decline earlier, some much later. And, as mentioned above, the decline does not occur at the same time in all sports. For example, it's well known that marathon runners can maintain peak performance well into their 30s. This doesn't mean that the decline is not occurring, it means that for certain activities it has less effect.