Young, single-sport athletes suffer more injuries and do not reach their full potential

Single sport participation is rising among young athletes. Many youngsters are not sampling other activities, and instead are focusing on only one in hopes of rising to levels of high performance in that sport. The main force driving this specialization is the cultural perception that getting an early start will help youngsters reach their full potential in the chosen activity.

We don't really know if this perception is accurate though. There is certainly anecdotal evidence that it worked for some athletes but no real research has been done to determine if it should be applied universally. Since sport talent is relative there is no standard to compare the efficacy of single- or multi-sport launches of young sporting careers. Who can say that a talented 10-year-old who specializes and reaches a high performance level wouldn't have been an even better athlete if the multi-sport path was chosen instead?

When the issue of specialization, which is what a single-sport athlete is doing, vs. generalization (participating in may sports and activities before specializing at a later age) is debated the experts favor generalization. However, the evidence is statistical and can't be applied to individual youngsters. So, when we try to promote generalization it stops being a statistical argument and becomes an individual one, which overzealous parents and coaches will almost always win.

Experts believe the generalist approach to athlete development is better. Here are three reasons why:

Specialists, the single-sport athletes, are more prone to overuse injuries. While usually not traumatic an injury that results from overuse of joints and muscles has the potential of becoming chronic. Chronic knee or ankle injuries in soccer, shoulder injuries in swimming, or elbow injuries in tennis can eventually end young athletic careers or prevent youngsters from reaching their full potential in a sport.

The generalists, or multi-sport athletes, develop a far richer repertoire of fundamental and sport movement skills at lower levels of their sport experience, which, when they do eventually specialize, adds to what we observe as athleticism in their performances: they seem more skilled, more athletic, better athletes than others on the field. Their performances seem richer perhaps because they have a deeper movement background to draw from.

Participating in a number of sports allows children to sample them to see which ones they actually like or may be good at. We all tend to like things that we do well and sport is no different so it's natural that children would want to play sports where they are better than others, where they get a chance to shine in front of their peers, parents, and coaches. However, if allowed to play only one sport in their formative years they are limiting themselves and may never discover if they might have been an ace basketballer rather than a discus thrower for example. Also, they miss out on the benefits to generalists noted above.

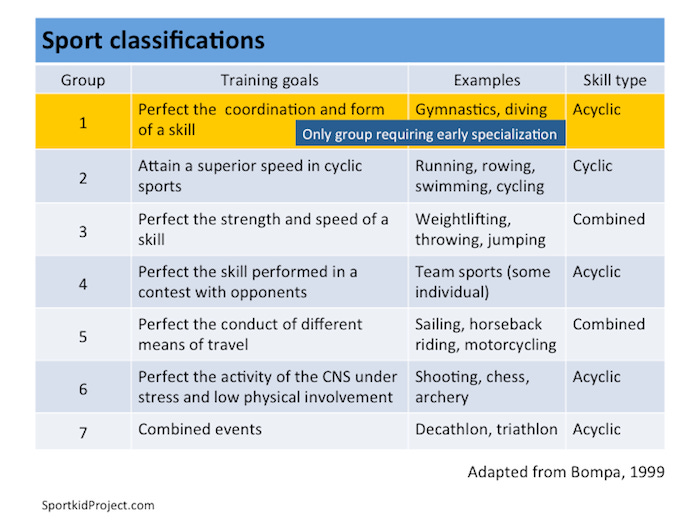

Related to the single-sport athlete is the classification of sports into early- and late-specialization groups, which I wrote about in When should athletes specialize in a single sport? Basically sports that focus on artistic or skill based performances such as gymnastics and figure skating require early specialization if youngsters are going to have a good chance to move into the high performance ranks. If you look at what's required to excel in these activities it's easy to see why early specialization is required: their skill set consists of the list of fundamental movement skills.

The fundamental movement skills are part of physical literacy (a brief summary of which appears in Physical literacy: The Holy Grail of health, wellness, and athleticism), and which are best learned between the ages of 7 and 12.

But the list of early-specialization sports is very small and no team sports are classified in this way (see figure). Team sports and other activities where performance depends on some metabolic or physical attribute such as strength or endurance are late-specialization activities. This means that specialization doesn't need to occur until later, usually in the mid-teenage years.

Cultural perception, not facts, drives inappropriate early-specialization

The zeitgeist in youth sport culture stresses the need to specialize early in a single sport if the youngster is ever to have a chance at college scholarships, national team selections, and possible professional careers. Getting a head start on the competition is seen as a good thing, if not actually a requirement.

We know that single-sport athletes suffer more injuries and that their prospects of long-term participation are not good but the argument, get a head start and performance will be even better later on, is one of those things that sounds like it should be true. It hard to convince parents and coaches that it isn't.

For most youngsters early-specialization does not achieve the expected result and, in some cases, sours the young person on the whole sport experience. A few years ago USA Hockey made a video introducing the American Development Model (ADM) that noted that athletes who start out as single-sporters later go on to participate in numerous sports when they discover that they either didn't like hockey as much as they thought or weren't as good as they hoped. They become generalists which is where youngsters should be starting, not ending up. It's the exact opposite of the hoped for development pathway.

USA Hockey knows that most young players will not play in the NHL, so the goal of the ADM was to create a pathway of participation in hockey that made sense to the long-term development of young players. The ADM is designed to give those with the potential to excel exactly what they need to move on to high performance as they age, and to provide a rich and wholesome experience for all youngsters. The ADM discourages single-sport focus until later, when it begins to make sense.

Specialization occurs at some point

The problem that an early single-sport focus presents is not that athletes are specializing but rather that they're doing it too early in the development process. To reach elite levels of performance specialization has to occur at some point.

In the Canadian Sport for Life Resource Paper, where a long-term athlete development plan is outlined in some detail, it is suggested that single-sport focus should not occur until about 15 or 16 years of age. Up until that point multi-sport participation should be encouraged. Athletes not interested in higher level participation can obviously continue participating in any number of activities; the point of the resource paper is to outline a pathway to high performance if that is the athlete's desire.

In the Path to Excellence, published by the United States Olympic Committee, athletes who participated in the Olympic Games between 1984 and 1998 were surveyed to determine if there were common pathways they used to reach the Olympic level. The report is fascinating to read and highlights several statistics relevant to this article:

Olympic athletes participated in a number of activities before specializing in the one where they eventually competed at the Olympic level (2.6 to 3.5 sports during the 10 to 14 age range).

Olympians reported an average of 3.3 to 3.4 days per week of activity in school-based physical education classes.

Olympians began their sport participation around 12 years of age with various sports and other activities leading up to actual sports 'training.'

The USOC report is old and deals with athletes who would have been brought up in the U.S. sports systems of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. Obviously, things have changed but it would certainly be interesting to conduct the survey again with athletes from the 2000 Games onward.

The question about specialization though is not, Should it be done? but rather, When should it be done? As athletes progress through their careers the amount of time they have to become who they want to be is limited and some activities have to be eliminated or relegated to a lower level of participation if continued improvement is to occur in an athlete's primary sport. Multi-sport participation is important to an athlete's overall preparation for elite performance in whatever their chosen activity, but it must occur at a sensible place in the developmental process. Athletes who skip the multi-sport stage of development are inadvertently missing out on an important part of the development pathway.